|

|

|

|

|

Estonian SS

|

|

Estonian 20. SS- Freiwilligen-

Grenadierdivision at Narva 1944

History by Heath Alexander

Formation

Citing a heritage that dates back to anti-communist partisans, the 20. SS-Freiwilligen-Grenadierdivision (later 20. Waffen-Grenadierdivision der SS) travelled a long, bloody and misguided path.

Following the Soviet annexation of the northern-most Baltic republic in June 1940, freedom fighters known as Metsavennad (Forest Brothers) fought a vicious guerrilla war against the Russian occupiers. These partisan bands contained numerous professional soldiers from the former republic’s 15,000 strong army.

|

|

|

The activities of this insurrection sparked odious reprisals from the NKVD and People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, including the formation of roving Execution Battalions to deal with the insurgents. The savagery of these reprisals helped polarize the Estonian populace behind the partisans.

At the time Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, an estimated 10,000 Estonian military personnel were conducting paramilitary operations against the Bolsheviks. These operations were so successful that by the time General Field Marshall Georg von Kuchler’s 18. Army reached the Estonian border it was nearly clear of Russian troops.

|

|

| Seeing the Third Reich as the salvation of an independent Estonia, a fateful decision was made to join the Nazis in their ideological crusade against Stalin’s socialist regime. |

|

The first step towards overt military cooperation with the German army was the establishment of an Estonian Home Guard to help combat bands of Soviet infiltrators. Poorly equipped and under trained, these regional units were organized into security groups and infantry battalions. Often operating close to the front lines, Home Guard units were routinely pressed into service by Wehrmacht commanders in the fight against the communists. Even poorly equipped the Estonians acquitted themselves well as the Nazi war machine rolled ever onward into Russian territory. |

|

As in other Nazi occupied territories, local collaborators saw it as beneficial to form a national legion to help further the cause of National Socialism and create the core of what was hoped to eventually become the new Estonian Army. The German High Command authorized the creation of an Estonian Legion in August 1942, paving the way for the practical formation of the unit in October of the same year. Against the wishes of many Estonian veterans, the new legion was placed under the control of the Waffen-SS. As a concession to Estonian objections concerning the Waffen-SS affiliation, the legion was almost entirely comprised of Estonians; soldiers, NCO’s and officers. It was this “Estonian Legion” that departed Pskov for Debica, Poland, arriving on 12 October 1942 with a total strength of 188 men.

Lieutenant Paul Maitla, the ranking Estonian officer in Debica, began training his men immediately upon arrival in Poland.

|

|

|

Within two weeks the Germans had sent five additional personnel, four officer training candidates and an acting commander, SS-Hauptsturmfuhrer Georg Ahlemann. By the end of 1942 a full six infantry companies awaited training in Debica before being sent to advanced training centres throughout Germany. This influx of personnel prompted the creation of 1. SS-Panzergrenadier Battalion “Narwa”, a fully motorized formation commanded by SS-Hauptsturmfuhrer Georg Eberhardt. Instruction progressed through the winter of 1942 after training officers from 3. SS-Panzergrenadierdivision “Totenkopf” arrived to conduct more operational schooling as every Estonian officer and NCO was assigned a German tutor. |

|

In spite of the “Death’s Head Division’s” involvement, not even these early Estonian volunteers received the level of indoctrination typical of other SS formations.

Volunteers continued to arrive from Estonia, swelling the Legion’s numbers to well over 1,000 by the spring of 1943. These sons of Estonia had excelled at their combat training, notably breaking all records for marksmanship at the Debica garrison. The Legion’s troops would soon be able to put this training to practice. The decision had been made to transfer 1. SS-Panzergrenadier Battalion “Narwa” to the elite 5. SS-Panzergrenadierdivision “Wiking”, currently stationed in the Caucasus Mountains but scheduled for transfer to the Ukraine. Battalion “Narwa” would replace the Finnish battalion recently recalled to Finland for political reasons.

|

SS-Panzergrenadier Battalion “Narwa” in Combat

Having rendezvoused with the Finns in mid April 1943 to assume equipment, the Estonians then continued on to the Donets Basin to join their new division. After linking up with the “Wiking” division during a refit, the units were sent to the Slovyansk area with the newly renamed Estonian SS- Freiwilligen (Volunteer) Panzergrenadier Battalion “Narwa” placed in divisional reserve. |

|

|

The battalion would soon see action however, as their positions southeast of Kharkov would thrust them into the crucible of fire.

In the summer of 1943, Wehrmacht leadership decided that the Soviet salient in the Donets River basin was untenable. To remedy this situation, Colonel General Walter Model’s 9th Army and Colonel General Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army would strike, from north and south respectively, at the heart of the bulge, the Ukrainian town of Kursk. Operation Citadel, as the German offensive was dubbed, would encircle the Soviet forces and eliminate one million communists. Unfortunately for the Nazis, those one million communists had been preparing defensive positions since the late spring and were more than capable of repulsing the fascist attacks of 5-13 July. This repulsion was soon followed in the form of Soviet counterattacks across the salient a week after the German advance had started.

|

|

So vicious were the Soviet counterattacks that 5. SS-Panzer grenadier Division “Wiking” was moved forward from Army Group reserve to stem the red tide. The brave men of Battalion “Narwa” were sent to the town of Izium on the southern end of the front line to hold until relieved. Having seen firsthand the battering taken by their predecessors, 46. Infantry Division, the battalion held no misconceptions about the hell they were moving towards.

Firmly entrenched by 17 July, the soldiers of the battalion were greeted that morning by an enormous Soviet artillery barrage. Soon after, combined arms attacks consisting of tanks and infantry smashed into the dug in Estonians. Nearly overwhelmed by their armored foes, the SS men were saved by the timely and accurate shooting of the battalion’s anti-tank guns, six in all.

|

| Within minutes of this initial attack half of the 20 T-34 tanks sent by the Soviets had been destroyed. After mopping up the remaining enemy infantry, the Estonians were only allowed a brief respite as another armored column advanced on their positions. Counted amongst the onrushing tanks were American lend-lease medium tanks, newly arrived from the harbour at Murmansk. These tanks too were knocked out by Estonian and German anti-tank guns, the tally for the day amounting to 28 destroyed armored vehicles. |

| 18 July followed a similar pattern as the previous day. Armour and infantry assaults reached the Estonian lines only to be thrown back after savage hand-to-hand and close-quarters fighting. Once again, burnt out tanks and Soviet infantry littered the field. A touch of desperation drove the Red Army on the 19 July to the extent that a fully armored assault was launched, absent of any infantry support. Numerous breakthroughs were achieved by the Soviet armour, cutting off the Estonian companies from their battalion HQ. Only the timely counterattack of SS-Hauptsturmfuhrer Eberhardt’s headquarters personnel halted the line’s disintegration and buoyed the morale of his men. |

|

|

Not even his subsequent death later that day could discourage the Estonian soldiers or keep them from carrying the day.

Having repelled the enemy in their sector, the Estonians paused to take stock of their situation. The battalion had taken nearly 600 casualties, 76 of them killed in action. The communists however, paid a higher price. The Red Army lost 7,000 men, killed and wounded, and over 100 tanks, some 74 destroyed by the Baltic soldiers. Although the Battalion “Narwa” achieved tactical victory on their section of the line, Operation Citadel was a strategic defeat for the Wehrmacht. An orderly withdrawal to the west followed the defeat at Kursk and the Estonians and the men of 5. SS-Panzergrenadierdivision “Wiking” found themselves northwest of Kharkov by the late summer.

|

|

Once the battalion had been returned to fighting strength, they were sent to Kharkov to halt an eminent Soviet breakthrough. From 12 August through the next week the Estonians halted repeated Russian incursions into their sector. Continuous shelling from enemy artillery ceased only long enough for Soviet infantry to crawl like ants towards the Baltic lines. Even repeated armored attacks couldn’t dislodge the doughty Estonians, thanks to their determination and the opportune arrival of several Tigers.

The arrival of autumn found the Battalion “Narwa” on the Mayeriyevka Front in western Ukraine, still attached to 5. SS-Panzergrenadierdivision “Wiking”.

|

| Although combat raged on a daily basis, the battalion received fresh replacements from Debica and managed to replenish their combat numbers. Having been ordered to winter in the town of Cherkasy, the Estonians were almost annihilated when the Cherkasy pocket collapsed in mid February 1944. As the “Wiking” Division was being withdrawn from the front for a complete refit, it was decided that the Battalion “Narwa” should be sent north to form the core of the 20. SS-Freiwilligen-Grenadierdivision, hastily being mustered near Narva to defend Estonia from Soviet reoccupation. |

|

20. SS-Freiwilligen-Grenadierdivision Combat History

Once the “Narwa” Battalion was incorporated into the new 20. SS-Freiwilligen-Grenadierdivision, the division was assigned to SS-Gruppenfuhrer Felix Steiner’s III SS (Germanic) Panzerkorps. Although severely under strength, the unit travelled nearly 1,000km from Kursk northwest to Narva in an effort to relieve the 9. and 10. Luftwaffefeld divisions at the Siivertsi bridgehead. After more than a week of brutal fighting against the Soviet 378th Rifle Division in late February, the Estonians managed to force the Bolsheviks back to the east bank of the Narva River. The division succeeded in holding the western bank of the river throughout the spring and was finally pulled back to rearm and reequip in May. Coincidently, German authorities implemented a local conscription program that netted 32,000 Estonian citizens. A large portion of these conscripts were added to the 20. Freiwilligen-Grenadierdivision, bringing their fighting strength back to a respectable 15,000 men.

In June 1944 the division was renamed the 20. Waffen-Grenadierdivision der SS (1st Estonian). Heavy fighting continued on the Narva Line through mid summer with the 45th and 46th Estonian Regiments particularly hard hit by Soviet infantry and artillery.

|

|

| Once he realized a major breakthrough was eminent, SS-Gruppenfuhrer Steiner ordered the panzerkorps to withdraw to the Tannenberg Line with the Estonians assigned to the Kinderheim Heights. Constant artillery and armoured attacks assailed the Baltic soldiers as they desperately held on to the land of the fathers. |

|

Leaving Estonia

Seeing the logic of retreating from Estonia to shorten the defensive line, Hitler ordered a withdrawal from the Baltic country in mid September. Instead of forcing the local military to retreat with them and defend the Reich, the Estonians were allowed to leave the Wehrmacht and defend their homeland. This achieved a dual purpose: as the Germans gave more ground in Estonia the loyalty of the Estonian forces was called into question; additionally, having seen the effectiveness of the Metsavennad first hand in 1941, the Nazis left a bloody partisan battle for the Soviets to fight as they pushed towards Poland. |

| The loss of manpower severely weakened the division again, forcing its removal from the line to Swietoszow, Poland. Here the division was refitted and sent German and Estonian replacements. After a quiet winter in Silesia, the Estonians were returned to combat duty on the Neisse River in late February 1945. With the Soviets crossing rivers almost daily during the Vistula-Oder Offensive, it’s no surprise that the division was encircled with the rest of the German 11th Army Corps near Falkenberg. It took two attempts in mid March to escape the pocket and only then at the expense of all the Estonian heavy weapons and equipment. |

| This marked the last major engagement of the 20. Waffen Grenadier Division der SS. By April of 1945 the division’s combat strength had been destroyed and the unit was moved south to Goldberg. As the Red Army lobbed shells at the Reichstag, the Estonian stranglers attempted one final breakout, this time to the west in an effort to surrender to American or British forces on the other side of the Annaberg Mountains. Lacking the vehicles necessary to outrun their Soviet pursuers, the remnants of the division were finally trapped and forced to surrender on 8 May 1945, the last day of the war in Europe. |

|

|

For the next fifty years the peoples of Estonia would pay for their complicity with the Nazis, a debt paid by their inclusion in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

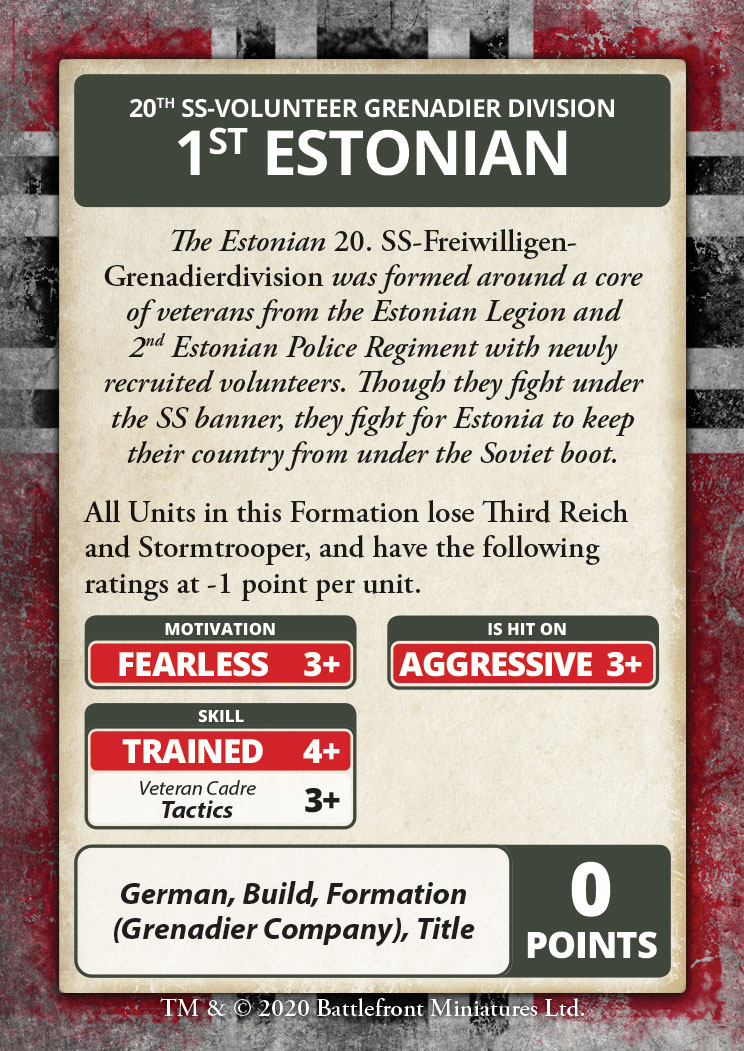

How to field the Estonians in Flames Of War

You can field the Estonians using the 20th SS-Volunteer Grenadier Division 1st Estonian Command Card and the Grenadier Company from page 16 of Bagration: German.

|

|

Last Updated On Thursday, March 4, 2021 by Wayne at Battlefront

|

|

|