|

|

|

|

|

Kamenets-Podolsky Pocket

|

Offensive in the Mud

The Kamenets-Podolsky Pocket

By Stephen Bernich

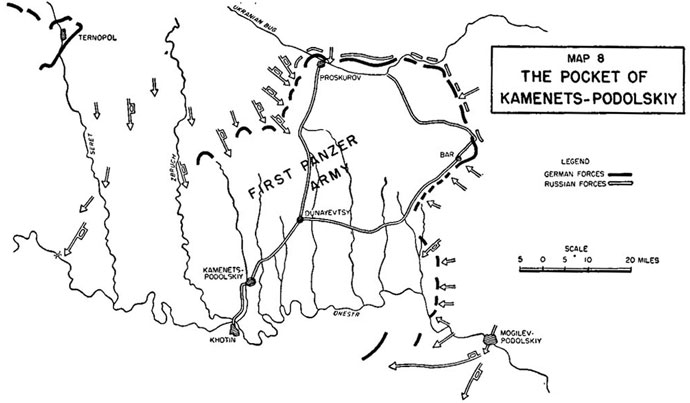

The Kamenets-Podolsky battles of late March and early April 1944, which have since become known as “Hube’s Pocket”, are remarkable for the fact that both the Soviets and the Wehrmacht could claim victory from their own perspectives. It is quite clear that they were a huge strategic victory for the Soviets. The near simultaneous thrusts by the 1st and 2nd Ukrainian Fronts, along with the 3rd and 4th Ukrainian Fronts to the south and the 1st and 2nd Beylorussian Fronts to the north had the combined effect of pushing the German lines back to southern Poland in a line down to the Romanian border. These lines were almost back to the original offensive lines that the Germans crossed in June of 1941. |

|

|

Additionally, the heavy axe blow of these combined attacks forced the total reorganisation of the southern German armies, Army Group South becoming Army Group North Ukraine and Army Group A becoming Army Group South Ukraine and forcing Generalfeldmarschal von Manstein out of his command of Army Group South.

However, at the same time the Soviets won their victory, the Wehrmacht won in the Kamenets-Podolsky pocket on the tactical level. The German 1. Panzeramee, the strongest Wehrmacht force of Army Group South, consisting of 18 divisions totalling approximately 200,000 men, was encircled by a superior Soviet force that was putting constant pressure on its borders as well as faced with blizzards and the Russian spring thaw or rasputitsa. In spite of all of this, the Germans were able to break free of the encirclement and live to fight another day, albeit weakened and minus the majority of their heavy equipment and armoured fighting vehicles.

At first glance, the Kamenets-Podolsky pocket can simply be written off as another in a string of the Red Army’s newfound strategy of double encirclement. Originating with the encirclement of Sixth Army at Stalingrad in the winter of 1942 and 1943, the Soviets developed the strategy of “double encirclement”. The idea was that one force would surround the enemy while a second force would encircle both the enemy force and the friendly surrounding force, forming a ring around them. This would allow the first force to concentrate on reducing the surrounded enemy while the secondary force could focus on stopping any potential rescue attempts as well as keeping pressure off of the original surrounding force. In fact, this very strategy was quite successfully played out only a month earlier with the surrounding of approximately 74,000 German soldiers at the Korsun- Cherkassy Pocket.These soldiers suffered brutally, at one point having the Soviet air force dropping incendiaries on a Russian village in order to burn them out, regardless of collateral damage to structures and civilians.

|

|

By this point the Germans would consider encirclement a fact of warfare. This was especially true on the Eastern Front where the vast duel of feints, thrusts, attacks and counterattacks would often leave groups of soldiers, whether large or small, behind enemy lines. These isolated groups were faced with the difficulties of not only fighting their way back to their own units, but also limited supplies of ammunition and food.

After the Korsun-Cherkassy battles of February 1944, the Red Army recognised its advantage against the beleaguered Army Group South. Forced to shift forces northward to counter the Korsun pocket offensive, Feldmarschall Erich von Manstein, commanding officer of Army Group South, was faced with weakening his Eighth Army by shifting Panzer divisions northward.

|

| Units were moved to both his powerful 1. Panzerarmee in the centre and 4. Panzerarmee in the north of the group, which had just taken a beating at Korsun. The resultant weakening of the southern portion of Army Group South was just what STAVKA, the Red Army generals, and Josef Stalin were looking for. A chance to take advantage of the Germans’ regrouping when they had little in the way of reserves was the perfect time to strike to continue pressing their advantage. The goal of this “winter offensive” in early 1944 was to push the Wehrmacht out of the Ukraine while the northern sectors, across from Army Group North and Army Group Centre had little comparable action due to weather, which stopped even Soviet advances. However, the Ukraine’s weather was a bit more temperate comparatively and the rasputitsa was enough of a break that even Soviet armoured vehicles could trudge through the endless mud and make solid gains. The planned offensive would keep the Wehrmacht on guard throughout their lines, the Germans would never really know if the Soviets would continue clearing the southern portion of the U.S.S.R up to and through Romania or if the focus would shift to the north and to liberate the Baltic States and the besieged Leningrad. The Germans would soon find out when Operation Bagration started in June. |

|

|

By mid February the 1st Ukrainian Front, under the command of Georgy K. Zhukov (taking over for the mortally wounded Nikolai Vatutin) and the 2nd Ukrainian Front, under Ivan Konev, were preparing for a near simultaneous offensive into Army Group South. The 1st Ukrainian Front would be responsible for an offensive along the lines of Proskurov and Chernovtsy, which would drive a wedge between 4. Panzerarmee and 1. Panzerarmee in the north while 2nd Ukrainian Front would advance along the Uman-Botoshany line, which would effectively cut off 1. Panzerarmee from 8. Armee to its south. The wider scheme of these attacks was to cut communications and supplies between the northern and southern German forces in the Soviet Union, each of which would be isolated and dealt with.

First Ukrainian Front would utilize shock group forces of the 13th Army, 60th Army, 1st Guards Army, 3rd Guards Tank Army and 4th Tank Army. Second Ukrainian Front would use the 27th Army, 52nd Army, 4th Guards Army, 5th Guards Tank Army, and 2nd and 6th Tank Armies. In addition, the 18th and 38th Armies of the 1st Ukrainian Front put up an active display of maskirovka (camouflage/concealment) to make it seem as if they were tasked with the major thrust when in fact they only had supporting rolls.

The German 1. Panzerarmee, on the other side, was made up of three Panzerkorps (III, XXIV and XXXXVI) with one Armeekorps (LIX) in support. Each of these had various Panzer and Infanterie divisions along with various other units, mostly at the brigade level.

|

| In addition, 509. schwere Panzerabteilung and Panzer Regiment Bäke (which had 37 Panthers and 14 Tigers) were on hand to provide much of the heavy support as many of the Panzer divisions were weakened from the fighting to relieve the Korsun pocket in February (1. and 11., both of III Panzerkorps, and 16. and 17. Panzer divisions). Additionally two SS units were with the 1. Panzerarmee, but both were weakened from combat as with the 1. SS-Panzerdivision “Liebstandarte Adolf Hitler” or from simply being left as a kampfgruppe while the rest of the division was moved to France as was the case with the 2. SS-Panzerdivision “Das Reich”. The infantry divisions in 1. Panzerarmee were in similar condition, some were combat ready and some were worn out and badly need of a break from combat. |

|

The true performer of 1. Panzerarmee, however, would be Generaloberst Hans Valentin Hube himself. Hube was a standout general in the Wehrmacht at the time, known as “Der Mensch” among the soldiers (“The Man”). He’d lost his left arm in combat and had been gassed as he rose the through the ranks to General Staff officer of the 7. Infanterieregiment during World War I. No stranger to war, he was also present at the encirclement of Sixth Army at Stalingrad where he was commander of 16. Panzerdivision and then XIV Panzerkorps. He had argued with Hitler about allowing Sixth Army to attempt to breakout of encirclement at Stalingrad, but Hitler saw that as a retreat. Hube himself was ordered out of Stalingrad on what was one of the last airplanes from Gumrack airfield. On his return from Stalingrad, he was promoted to General der Panzertruppen.

This experience led Hube to believe his 1. Panzerarmee was going to face encirclement once the Soviets began their offensive at the beginning of March. In fact, he ordered all administrative and non-combat personnel to the rear so there would be fewer mouths to feed in the case of low supplies. In addition, he was faced with fuel shortages. All fuel was siphoned from non-combat vehicles, which were then destroyed. Aside from the armoured fighting vehicles, 1. Panzerarmee was able to make do with the horse and wagon for any other transportation.

These preparations were completed just in time. The 1st Ukrainian Front began its attack on 4 March, while 2nd Ukrainian pushed off the next day.

|

|

|

The initial attack on the 4 March saw rapid gains by 3rd Guards Tank Army, 4th Tank Army and 60th Army as they ripped through the front between 1. Panzerarmee and 4. Panzerarmee. Within three days they were approaching Proskurov and Tarnopol.The Soviets also had cut the Odessa-Lvov rail line at Chortkov, which was 1. Panzerarmee’s main source of supply and contact with forces north of it. With this essential artery cut, the next Soviet goal would be Tarnopol. However, heavy resistance by the German garrison left in the city and a German counterattack meant to blunt the offensive caused the rapid Soviet advance to simply outflank Tarnopol and move west.

Meanwhile, 2nd Ukrainian Front met with similar success as 27th Army, 52nd Army and 4th Guards Army spearheaded the offensive with 2nd and 5th Guards Armies and 6th Tank armies in reserve to exploit any breakthroughs.

|

|

Their objective was to reach the Southern Bug River and the Dniester River as soon as possible with Podolsky and Mogilev as the initial goals. This move drove a wedge between 1. Panzerarmee and 8. Armee to its south.

By 13 March, Zhukov’s left flank, spearheaded by 1st Guards Tank Army and 4th Tank Army with the 60th Army and 1st Guards Army in support focused on taking the city of Kamenets-Podolsky.

|

|

|

Kamenets-Podolsky was the historic capital of the Podillia region of the Ukraine on the Smotrych River, a tributary of the Dniester. Taking into account the successes of 2nd Ukrainian Front, a new plan was in order as both Zhukov and Konev recognised the possibility of encirclement of 1. Panzerarmee.

New operations began on 20 March, with a westward push by 3rd Guards Tank Army and 1st Guards Army continuing towards Chernovitsy. The attack on Cernovitsy further preoccupied 4. Panzerarmee, who were trying to maintain a hold on Lvov. However, 1st and 4th Tank Armies, with 18th and 28th Armies in support, furiously drove south through the Zbruch river valley to reach the forces of 2nd Ukrainian Front between the Zbruch and Serets Rivers (tributaries of the Dniester). This move cleared out German strong points between the two rivers as well as effectively cutting off the 1. Panzerarmee by 25 March when these Soviet forces met with 40th Army from 2nd Ukrainian Front, which was swinging northwards.

By 20 March, 1. Panzerarmee could see several Soviet armies just across the Dniester River to its immediate south. It held a single bridgehead at Khotin. The rapid advance of Konev’s 2nd Ukrainian Front had succeeded in pushing German 8. Armee’s divisions further southwards towards the Danube River, the Romanian border and the Carpathian Mountains. In fact, 2nd Ukrainian Front reached the foot of the Carpathians themselves by 25 March.

|

|

The encirclement was complete by 25 March with 6 Soviet armies (3rd Guards Tank, 4th Tank, 1st Guards, 18th, 38th and 40th Armies) applying pressure to Hube’s force. At the same time, the external encirclement, held by 13th and 60th Armies and 1st Tank Army, was designed to force the German 4. Panzerarmee and 8. Armee back and unable to attempt a rescue operation. It is at this point that 1. Panzerarmee was probably very lucky to have Generaloberst Hube in command and Field Marshal Erich von Manstein in command of Army Group South. Both men were proponents of “mobile defensive” operations which allowed a large force to attempt a break through of encircling forces while maintaining a strong backwards defensive posture from rear guard units. In fact, |

|

Manstein was destined to lose his job over the several times he butted heads with Hitler about allowing encircled troops to attempt breakouts. Hitler consistently saw these manoeuvres as retreats, especially after he had given specific orders that all urban centres be held and turned into Festung Platz (fortified city). These orders forced the garrison at Tarnopol to hold out to the last man (which it almost did) and forced 1. Panzerarmee to maintain its position around Kamenets-Podolsky in spite of increasing pressure from the Soviets.

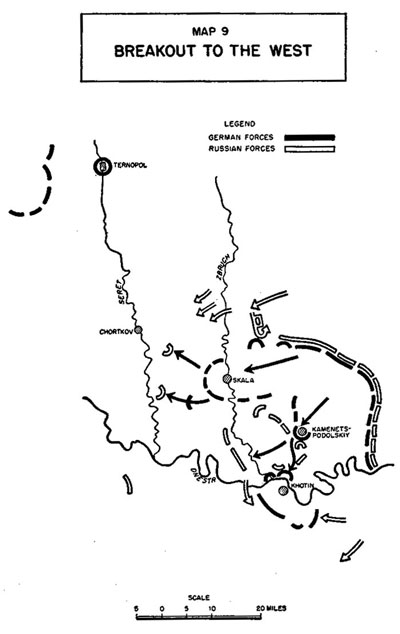

However, there were weaknesses in the rings surrounding the German 1. Panzerarmee and it was these that allowed Manstein and Hube to come up with a functional plan to allow the surrounded divisions to survive. There was a ten-mile gap between 1st Guards Army and 4th Tank army, which had only 60 combat worthy tanks left. Additionally the 4th Tank Army and the 30th Rifle Corps (part of the tank army command group) were critically low on fuel. Meanwhile, the 18th Guards Corps, part of the outer encirclement, was holding 75 miles of front opposite 4. Panzerarmee. In spite of these weaknesses, the Soviets immediately began their compression with constant attacks on all sides of the 1. Panzerarmee bubble. With 1. Panzerarmee still holding the bridge over the Dniester at Khotin, it seemed obvious to both Zhukov and Konev that at some point Hube would attempt an offensive south, have his army cross the Dniester and then head for the relative safety of the Romanian border. The two Soviet commanders began to shift forces southward to prepare for a breakout.

|

|

Manstein and Hube, seeing the strengthening of the southern forces, began to devise a counter plan. In spite of the strength of the forces to the north and west of 1. Panzerarmee and the distance of 125 miles to 4. Panzerarmee’s lines, Manstein wanted Hube to breakout west. This would force 1. Panzerarmee to fight its way out of encirclement against some of the strongest forces surrounding it. However, with Zhukov and Konev’s strengthening of the southern forces across the Dniester, Manstein and Hube counted on surprise to achieve their goals. The move west would take 1. Panzerarmee across broken terrain and force the army to cross three rivers (the Zbruch, the Seret and the Strypa) to reach safety but these factors would also affect any Soviet counterattacks and were looked on as a force equalizer. All of this, when weighed against the southern escape route, seemed to make breaking west less sensible. To the south, Soviet forces were gathering but were not yet at full strength. The German 1. Panzerarmee already had a useable bridgehead and the safety of the Romanian border was not far. However, a break south would take 1. Panzerarmee out of operational readiness for Manstein’s Army Group South, which had few divisions left in reserve and would lose its strongest formation.

Manstein presented his case to Hitler time and time again before Hitler finally relented, contrary to his previous Fuhrer Order # 51, requiring the defence of all cities. On 25 March Hitler gave Hube authority to breakout as well as giving Manstein command of II SS-Panzer Korps, consisting of 9. and 10. SS-Panzer divisions (Hohenstaufen and Frundsberg), 100. Jäger and 367. Infanterie divisions, which would fight their way from 4. Panzerarmee lines to try and reach the encircled troops.

|

|

|

Hube immediately began preparing the forces under his command, simultaneously shorting his defensive lines by withdrawing away from the Soviet forces. This allowed his men to defend in force against any local attacks and maintain operations between divisions and command points. He also repositioned his forces into three distinct kampfgruppen, the first and second being northern and southern attack groups. The Kampfgruppen were to carry out the initial breakout west while a rearguard group would fight aggressive fighting withdrawal type engagements. The North and South spearheads were lead by Panzerkampfgruppe Bäke and his Panthers as well as the other panzer divisions. The Tiger companies of the 509. schwere Panzerabteilung dominated the rearguard. The idea was that Hube would need to move his entire force of 200,000 men and their equipment like a blob or an amoeba, stretching west, while the eastern portions contracted and followed suit. This pattern was to continue through the rear of the surrounding Soviet divisions, then across two rivers and the muddy terrain between them.

Early afternoon radio reports of 28 March indicate that 1 Panzerarmee Headquarters Units, III Panzer Korps, and at least two other panzer divisions were operating close to the Dniester River crossing at Khotin and were making preparations to cross the bridgehead and break out south. Additional Soviet reconnaissance indicated German pioneers readying the crossing point for traffic.

|

|

Believing his guess was right; Zhukov relaxed his other armies and focuses all attention on the southern units, mostly from Konev’s army, as well as reinforcing them.

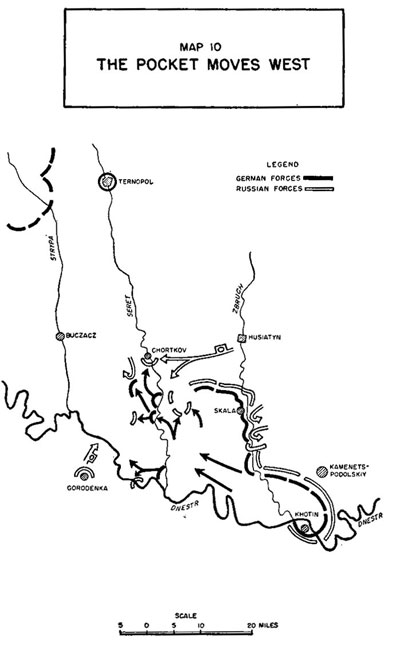

This played perfectly into Hube’s plan as the night of 28/29 March, Panzerkampfgruppe Bäke was given the order to break west with 1. Panzerarmee’s entire force behind it. To make matters worse, a blizzard began the night of 28 March blanketing everything in thick white snow, an added hindrance that slowed movement but also provided concealment. By 29 March, the first Panther battalions of 1. Panzerarmee had seized three separate bridgeheads across the Zbruch River and were advancing against Soviet defenders in the valley between the Zbruch and the Seret. The rearguard of 1. Panzerarmee was only a day’s travel behind its advance elements. The forward forces held the line at the Zbruch bridgeheads just as the Seret River was reached.

|

|

It was at this point that Zhukov and Konev realised they’d been tricked. The advance west of Hube’s army and reports that II SS-Panzerkorps was attacking aggressively towards Kamenets out of 4. Panzerarmee to the north left no doubt that the southern breakout was simply deception. Immediately, intense attacks were launched against the 1 Panzerarmee’s rearguard and an attack across the Dniester northwards by Soviet 4th Tank Army was ordered. However, the 4th Tank Army suffered against the tanks of the German Southern force that was advancing in the area and the fighting rendered it ineffective by 31 March.

The Soviets excelled at making up time and territory in the quagmire of the muddy terrain, now coated with the heavy snows of the blizzard, which lasted until 1 April, but Hube’s army had one further ace up it’s sleeve. The Luftwaffe was providing active resupply flights, in spite of the weather, either to small airstrips to land and pick up wounded or at the least airdropping supplies to the troops below.

|

|

|

This kept 1. Panzerarmee fuelled and supplied enough for the constant moving and fighting, both day and night, over the two week running battle.

II SS-Panzerkorps slammed into the weakly held lines of 18th Guards Corps around Podgaitsy, smashing through on 4 April. The next day, advance elements of 1. Panzerarmee Army’s breakout force met elements of the II SS-Panzerkorps, which then swung north in an attempt to relieve the besieged garrison at Tarnopol, still holding on to the last man per Hitler’s instructions. The effect of this was that all the garrison were killed or captured as Tarnopol suffered under Soviet bombardment, the II SS-Panzerkorps had simply arrived too late. Over the next few days, elements of 1. Panzerarmee pushed forward into 4. Panzerarmee’s lines at and around Buczacz on the Strypa River. The breakout had been secured, but fighting continued for another two weeks into April as all of 1. Panzerarmee’s divisions and men were successfully withdrawn. Total losses in men to the Soviet forces are unknown but the vehicle count is very accurate at 357 tanks, 42 assault guns and 280 artillery pieces destroyed.

The 1. Panzerarmee had escaped with most of their manpower and remained a viable fighting force. They re-established a new front line from the Dniester River up to the town of Brody. They suffered minimal casualties but lost most of their heavy equipment throughout the almost month long battle. They suffered few losses to “kessel fever” like the Germans did in Stalingrad. Hube’s policy of keeping all of his troops informed as to what was going on, the constant resupply effort by the Luftwaffe and the fact that, despite being surrounded, they were constantly on the move and attacking, kept any Germans from real thoughts of desertion or at worse, suicide.

|

| This was a lone bright star in the Wehrmacht’s Russian campaigns of 1944, where otherwise there was little to cherish as the Soviet onslaught continued to pound away and push the Germans back. To further dampen the relief of having saved 1. Panzerarmee, the entire Wehrmacht would suffer the loss of Generaloberst Hube when, after receiving Diamonds for his Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords, his plane crashed in the Austrian Alps after leaving his medal ceremony on the way back to his command. |

|

Playing Hube’s Pocket in Flames Of War

If players want to recreate the encirclement and subsequent breakout of the Kamenets-Podolsky Pocket, they can do so rather simply with a series of three or more games.

To begin, players should use the Bridgehead Mission from the main rulebook with a Soviet T-34 Tank Battalion attacking the Germans in the cauldron or “kessel”.

The second game could be a Breakthrough mission with a German Panther or Panzer IV Tank Company or Panzergrenadier Company breaking through Soviet lines. Any Soviet company would be appropriate in this case.

Finally, the third game could be a Rearguard mission with a German Tiger Tank Company withdrawing under the pressure of Soviet T-34 Tank or Motor Rifle companies.

Players should use snow terrain rules for most of the games, which of course, slows things down but adds realism to the circumstances of the events. Due to the sheer size of the armies involved in Hube’s Pocket, it is probably impossible to truly recreate the drama of the breakout, but perhaps players could play a bigger multiple company games to simulate the various companies supporting each other whether on the attack or defence.

These are, of course, mere suggestions. The scope of the actual engagement was so large, with 200,000 Germans and approximately 500,000 Soviets involved, that players could go about it in almost any fashion they like, using very possibly any and all of the missions and all available companies for both the Soviets and Germans. |

Last Updated On Friday, March 12, 2021 by Wayne at Battlefront

|

|

|