|

|

|

|

|

|

The Netherlands at War 1940

During World War I the Netherlands managed to stay neutral. This feature and the atrocities committed by the Germans in Belgium in World War I led to a strong anti-war commitment in Dutch politics, symbolised by a broken rifle displayed by the supporters of this posture. It was hopped that a neutral stance deter aggression. Although some advocated a total abolition of the armed forces, this did not happen, but the Defence budget saw extensive cuts. The result was that the armed forces modernisation was slowed down and the conscripts received less training and were in fewer numbers.

Rearmament

With Hitler’s rise to power the international situation deteriorated. Finally the Dutch politicians realised that the state of defence needed improvement. A programme was started in order to rearm. As weapons producing countries did so too, the Dutch found it hard to get the arms and equipment they wanted and needed. Much of the weaponry and ammunition was ordered from German companies, or their foreign-based subsidiaries. This led to many delays.

The British for their part were not too keen to send weaponry and ammunition to the Dutch, as Dutch neutrality was of no use to the British. Besides, the Dutch had refused to extradite the German Kaiser after World War I.

|

|

The Netherlands 1940

Early-war Intelligence Briefing covering the Netherlands forces facing the German Invasion.

History by Victor van Zutphen

Briefing by Victor van Zutphen and Wayne Turner

The Netherlands 1940 Intelligence Briefing PDF...

Modelling article coming soon...

|

|

Nevertheless the army mobilised in 1939 and preparations for the defence of the country were initiated. This meant that in some areas the troops had to dig fortifications, consuming precious time. On the other hand, these troops had the benefit of said fortifications, when the Germans arrived. Because of the neutrality, which was still the main over-riding strategy, for political reasons the defence had to be arranged facing all possible directions. If nevertheless attacked, the plan was for the Netherlands to ally itself with the enemies of the attacker. Note that during the Phony War both German and Allied aircraft that entered Dutch airspace were shot down!

Defensive Plan

The Dutch realised that they could not withstand a German onslaught for a prolonged period. The idea was to hold on until relieved by a more powerful ally. It was expected that two to three months would be sufficient. In retrospect this must be considered too optimistic given the amount of ammunition and manpower available.

|

|

|

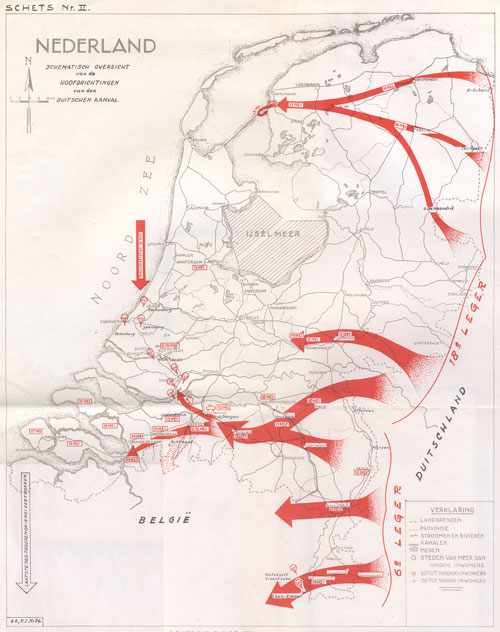

The idea was to use the time honoured Vesting Holland (Fortress Holland), the western part of the country, ultimately defended to the East by the New Dutch Water Line. This line was strongly defended by large inundations or floods. To the South, Fortress Holland was defended by the wide rivers like the Maas (Meuse). To create more depth a defensive line was created further to the East, running North-South. The Grebbelinie (Grebbe Line) ran from the IJsselmeer (Lake IJssel) via Amersfoort, Veenendaal, Grebbeberg (near Wageningen) and Ochten to the river Waal. Here it linked to the Maas-Waalstelling (Meuse-Waal position), which linked to the Peel-Raamstelling. The latter ran from North to South via Ravenstein, Grave, Mill, Heleenaveen, Meijel and Weert to the border with Belgium.

|

|

Belgium however refused to link up to this line and created a defensive line further west, leaving a gap through which the Peel-Raam position could and eventually would be flanked. Secret negotiations with the French asking them to fill the gap failed. The French were only prepared to move up to Breda in order to protect their own flank. In the end the task of filling the gap was given to the Lichte Divisie (Light Division). This was a bicycle mounted mobile reserve behind the Peel-Raam position.

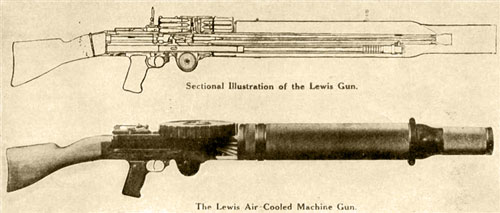

Weapons

At the outbreak of the war the Dutch had a variety of weaponry and equipment, ranging from obsolete to modern. Some newer systems were available as ordered (notably the 2 tl AA guns), others in limited numbers (Solothurn Anti-tank rifles). The artillery had both new and obsolete guns. It is however a myth to say that the Dutch army was completely outdated, as it would be equally wrong to say that it was state of the art. Both Belgium and France used old artillery pieces to make up the numbers needed, as did the Germans. More worrying was the limited amount of ammunition available, insufficient for any prolonged battle.

|

|

The Positions

As mentioned the Dutch intended to hold on until relieved by an ally. They realised that not all of the country could be defended. The troops along the border were very thinly spread out, their sole role being to sound the alarm in case of a German attack. Further inland were yielding lines, designed only to slow the enemy. Notably the Wonsstelling guarding the entrance to the Afstluitdijk (Enclosure dam), the IJsselstelling, guarding the approach towards the Grebbelinie and Maaslinie, guarding the approach towards the Peel-Raamstelling.

The purpose of these lines was to slow the German advance as much as possible in order to allow the main lines of resistance to prepare themselves. Before the war the Dutch Commander in Chief, Generaal Reijnders had wanted both the Grebbelinie and the Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie (New Dutch Water Line) to be strongly fortified. Should the Grebbelinie fall, the army would have a strong and prepared position to fall back on. When the government would not grant him the necessary financial means, Generaal Reijnders resigned.

|

| Generaal Winkelman (retired) was called back to active duty and succeeded Generaal Reijnders as Commander in Chief. He was forced to choose between the Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie and the Grebbelinie. As the works on the Grebbelinie were more complete than most, the choice fell upon this line as the main line of defence for the Vesting Holland. Most of the Grebbelinie had extensive inundations (flooded areas) in front of the fortifications. Near the Grebbeberg (‘mount’ Grebbe) however, the land was too high to be flooded. Here the Dutch, rightly, expected the main German attack on the Grebbielinie. The Peel-Raamstelling also had extensive protection by inundations. Near Mill however there was also a dry sector. It was hoped that the latter line would hold the Germans, but the main defensive effort would rest on the Vesting Holland. |

The German Plan

The Germans had planned to overrun the Netherlands in one day and then turn south to cut off the French and British forces. Furthermore General Student wanted to prove that his airborne army was capable of more than small scale actions. He was allowed to try and end the war in the Netherlands within hours. To this aim a large force of the 22nd Airlanding Division (22. Luftlandedivision) would land on the three airfields that surrounded Den Haag (i.e. not the Dutch capital, but the seat of government, The Hague). These troops were to cut off Den Haag from all directions, breaking the Dutch government’s control over its forces and hopefully capturing the Dutch queen, government and high command, forcing them to surrender and leading the country’s military to lay down their arms, all within hours after touching down.

|

|

|

One idea mooted was to bring a bouquet of flowers for Her Majesty the Queen, but she never got it! The German airborne first of all had to despatch one reinforced company to seize of the Belgian fortress Eben-Ebmaël, as its guns could fire upon German forces crossing of the river Maas at Maastricht. The rest of the airborne army was sent to the Netherlands. Other forces were detached to take the bridges at Moerdijk, Dordrecht and Rotterdam, thus opening the south flank of Vesting Holland for the army (Monty’s idea in 1944 wasn’t totally original).

On the ground, the German field army was to attack in four prongs. The first (mostly cavalry) was to occupy the northern provinces and find a way either to cross the IIsselmeer or to cross the Afsluitdijk. The second was to attack the IJssellinie and subsequently the Grebbelinie. The third was to attack the Maaslinie, subsequently the Peel-Raamstelling and to attack the Vesting Holland from the South, creating a pincer with the second line of attack. The fourth line of attack was only aimed at the Netherlands (province Limburg) in order to gain access to Belgium. It would attack the Maaslinie, cross the river and proceed into Belgium.

|

|

The Battle for Den Haag:

‘Germany’s first defeat’

A historian once dubbed the German actions around Den Haag ‘Germany’s first defeat’ in WWII. This may be a bit over the top, but the fact is that not only did the German airborne troops not reach any of their objectives in this field of operations, they were forced on to the defensive.

22. Luftlandedivision (22nd Airlanding Division) was charged with attacking Den Haag from three sides and effectively cutting it off from the rest of the country, disabling the chain of command. Furthermore, special task forces were to make their way into Den Haag and to capture the Dutch Queen, government and high command. To this end the division received one battalion of Fallschirmjäger (paratroops).

|

|

At the time three airfields surrounded Den Haag. To the North lay airfield Valkenburg, to the West Ypenburg and to the South Ockenburgh. Valkenburg and Ypenburg were first attacked by Stuka dive bombers. As well as damaging buildings these attacks also did much to shatter the morale of the troops guarding these airfields. The air attacks were soon followed by German Fallschirmjäger. These landed not quite on top of the airfields, but in open ground very close by, taking full advantage of the confusion following the Stuka attacks. Both airfields were quickly seized and brought under control. Although Ockenburg was not bombed the Fallschirmjäger had the element of surprise on their side and quickly took the airfield.

The next stage of the plan was to bring in the airlanding infantry. These men were not highly trained elite Fallschirmjäger, but regular (light) infantry that had been trained to quickly disembark from Ju 52 transport airplanes. The combined force was to set out to lock down Den Haag.

At this point things turned sour for the Germans. As a reaction to the German airborne actions in Norway the Dutch had reinforced the defence of these airfields by adding HMG nests covering the runways. This was unknown to the Germans. The Fallschirmjäger had tried to knock these nests out, but stood no chance in the open field. The effect was that incoming Ju 52s had to land through a hail of fire. Not only was this lethal for the airlanding troops, it also had a devastating effect on the state of the aircraft. Many of these were unable to take off again to make space for the following wave. Before long the airfields were blocked with broken down planes, preventing any new ones from landing. To add to the problems, came the fact that Valkenburg airfield was rather new and the ground still too soft for heavier aircraft. The Ju 52s tended to sink too far into the ground to move off. As a result many Ju 52s looked for alternative landing places. Grassy meadows in the vicinity seemed a good idea. However these were too soft to provide a solid landing ground for a fully laden Ju 52. Many upturned upon landing. Others tried to land on the (two lane) highways. In such cases, the landing successful, but taking off was no longer possible. Finally many saw the sandy beaches as a good alternative. Again landing was hazardous, leaving many planes upturned in the soft sand. Again, there was no chance of taking off again. Finally the German command decided not to send in any more waves of troops. The commander of the operations on the ground, Graf Von Sponeck, was supposed to land on Ypenburg. He found himself landed on a beach near Ockenburg, to where he headed.

|

|

This was one of the problems the Germans faced. The reaction by local, most junior, officers was swift. Taking initiative local units were rushed to the scenes, blocking exits of the airfields, trapping the Germans. These actions were performed by officers with whatever units they could muster, from trained regulars to recruits.

Once the picture had become clear to higher command the matter was dealt with in a more coordinated manner. What artillery was available was first brought to bear on Ockenburg, supporting an infantry attack on the airfield and demolishing more stranded Ju 52s in the process. The attack was a success. Von Sponeck withdrew with his men to nearby woods where they dug in.

|

|

|

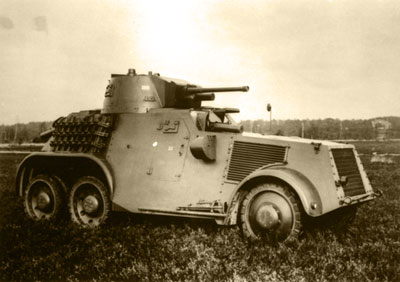

Subsequently artillery was made available for both Ypenburg and

Valkenburg. The attack on Ypenburg was also supported by armoured cars.

Eventually the Germans were overcome. Many were taken prisoner. Most of

them, notably the highly trained Fallschirmjäger, were put on transport

ships to Britain.

Meanwhile, the pressure on Von Sponeck’s unit was increased, forcing him to withdraw again and again. Taking up stragglers on the way his unit was finally encircled in the village Overschie. The Dutch conducted a final attack on Overschie. They managed to penetrate the German positions, when the order came to surrender! The Dutch government had surrendered following the Rotterdam bombing disaster and the German threat to do the same to Utrecht.

The taking of bridges at Moerdijk, Dordrecht and Rotterdam

The Germans intended to take the Vesting Holland by a pincer movement. One attack was on the Grebbelinie, the other entered Vesting Holland from the south and linked up with the troops that had landed around Den Haag. In order to achieve this German armoured forces had to quickly break through the Peel-Raamstelling and race via Dordrecht to Rotterdam. As later in the war, bridges were essential and speed was of the essence. They had to be taken intact and held until relieved. General Student entrusted this operation primarily to his Fallschirmjäger, supported by airborne infantry.

In the early morning of 10 May 1940 Stuka dive bombers attacked the Dutch troops guarding both ends of the Moerdijk bridge. Although their senior officer was aware that the Germans had crossed the border, he did not anticipate any Germans reaching this position soon. Hence he hadn’t put his troops on alert and most were sleeping. The effect of the Stukas under these circumstances was devastating. A large force of Fallschirmjäger dropped close by both positions and rushed to their objective. Many Dutch soldiers were captured still in their nightwear. This bridge was securely in the hands of the Germans.

|

|

Further north, one company of Fallschirmjäger did the same at the bridge in Dordrecht. In Rotterdam, the Germans could not land a large force of paratroopers in the middle of the town to secure the bridge immediately. To prevent the Dutch from blowing the Willemsbridge a taskforce of air landing troops landed with seaplanes near the bridge to take it. The main force dropped onto Waalhaven airfield after a preliminary Stuka attack. A swift Dutch counterattack prevented the taskforce from reaching its objective. Finally, the Germans barricaded themselves in an office building on the northern bank, near the bridge.

|

|

This force was unable to move, but could prevent Dutch forces crossing the bridge. Meanwhile, the attack on Waalhaven was successful and soon the Southern part of Rotterdam was held by the Germans, yet the bridge was still contested.

Taking the bridges was one thing; keeping them was a totally different matter. The Dutch High Command realized the danger and was keen to put an end to it. In the South, light mobile forces were sent to keep the Germans where they were, whilst the French would send an armoured column to drive them out. This column however was bombed and strafed by the Luftwaffe, forcing it to withdraw. The Dutch on the southern end held their position, but were not strong enough to force the Germans off the bridge. A Dutch attempt to bomb the bridge failed; one bomb missed the target and the other failed to explode.

In Dordrecht, however, the Dutch were swift to respond. This was mostly on the initiative of several junior officers and NCO’s. The German Fallschirmjäger were in more than a little trouble and clung on by their fingernails, yet cling on they did. Between Moerdijk and Dordrecht more Fallschirmjäger dropped as support to both the attacks on Moerdijk and Dordrecht. These troops started to make their way into Dordrecht. Fierce street fighting broke out. On the Dutch side the Light Division (cyclists) was ordered to ‘put an end to it’ and joined in the fight. On the German side General Student sent as strong a reinforcement as he could muster once he secured his position in Rotterdam. In this he was helped by the fact that the air landing troops originally intended for Den Haag had been allotted to him once it was realised the airfields around Den Haag could not receive them and they had marched from alternative landing sites.

|

In Dordrecht, the bridge was still contested despite fierce efforts on both sides to gain the advantage. This situation lasted until German armoured units finally linked up with the Fallshirmjäger in Moerdijk and subsequently raced to Dordrecht. Here they found that the Dutch had mustered some anti-tank guns and put them to good use knocking out several German armoured cars.

|

|

|

Nevertheless the influx of German reinforcements

sealed the fate of the Dutch in Dordrecht. However, the experience with

the Dutch anti-tank guns would have consequences though in Rotterdam.

In Rotterdam, both sides had tried in vain to take the Willemsbridge. Both had good positions to deny the other access to the bridge. The Germans were very anxious that the Dutch might blow the bridge, which the Dutch indeed intended to do, but were unable to. When the news arrived at Student’s HQ that the armoured troops had reached Dordrecht the first idea was that these would immediately charge across the bridge. However, the experience in Dordrecht and the fierce Dutch resistance made the Germans weary of this plan. Student and, following the link up, his new superior Schmidt reckoned that the Dutch positions on the northern end of the bridge had to be bombed prior to the assault in order to knock out any anti-tank defence. This idea coincided with growing impatience within German Higher Command about the prolonged fighting in the Netherlands.

They had planned to attack the Belgians, French and British from their northern flank as soon as these troops became free after the taking of the Netherlands. The prolonged fighting had already led to the diversion of Luftwaffe units intended for the attack from the east on Belgium in favour of the operations in the Netherlands. Göring himself urged for a swift end to the fighting with whatever means necessary. Even Hitler had given instructions to get it over with. So it was decided that the Dutch positions in Rotterdam opposite the bridge were to be bombed.

|

|

The only bomber unit available at that point was a unit with He 111 bombers. It was decided that these were to take off and keep contact with their base as long as possible, so the raid could be called off in case of a surrender. As a secondary safety measure red flares would be fired in case the raid was to be called off. The Germans had demanded the surrender of Rotterdam, threatening to destroy the city otherwise.

From the Dutch point of view the situation was not hopeless. Although they could not take the bridge, they could effectively keep it closed to all German traffic. German airborne attacks on Den Haag were successfully beaten off and the loss of the bridge would mean the southern perimeter of Vesting Holland would be breached.

|

|

The Dutch played for time. The (in fact second)

ultimatum was turned down, as it bore no rank, name or signature of the

German commander. However, the Germans were led to believe that the

commander of Rotterdam, Scharroo, was willing to negotiate a surrender.

Upon this news Schmidt gave word to the Luftwaffe that the bomber attack was to be postponed. The Heinkels however were already airborne and out of radio contact with their parent airfields. Schmidt was not informed about this. He sent out a new ultimatum this time properly ‘signed, sealed and delivered’. Before the ultimatum had run out though Schmidt noticed the Heinkels approach. Immediately he gave the order to shoot the red flares. One bomber group noticed a red flare and broke off the attack. The other did not and bombed its target, in the centre of the old city of Rotterdam. As fires broke out the dry wood in the old buildings did the rest. The fires spread beyond the capability of any fire brigade. Scharroo believing this to be a deliberate act by the Germans and fearful of more damage to the population, surrendered the town to the Germans. The Southern perimeter of Vesting Holland was breached.

Allied support

Like the Poles, the Dutch expected to be helped by the foes of whoever attacked them. Once the Germans attacked, both the British and French would become Dutch allies. However, neither country was ready for war when the Germans launched their attack. All the forces that the British could muster in significant numbers were already deployed in northern France and, according to a planned move into Belgium to take positions there. All the British offered in assistance was some bombing sorties and some special actions aimed at rescuing as much gold bullion as possible from the banks and demolishing oil supplies near Rotterdam.

The French supplied a larger force in support of the Dutch efforts. That is to say, the French realized the threat to their northern flank should the Germans managed to break through the Dutch southern most defences. To secures this flank an armoured mobile force was sent to Holland. But at the border between Belgium and Holland they encountered the first of many setbacks.

|

|

When the alarm was raised in the Netherlands all border units were ordered to place and prime their road obstacles and mines. Although the troops facing southwards towards Belgium did not see the point of doing that when the attack came from the east, no one questioned the order and it was duly executed. The French lost precious time clearing these obstacles and making their way towards Breda.

At Breda, a meeting was held with the already stressed commander of the Peel division whose force was already retreating. It was decided that part of the French force would move northward and take up position amongst the Dutch in the more northerly part of the intended new line.

|

|

|

Had they done this, they would have met the German light armoured troops

that were racing towards Moerdijk. However, the commander of this

detachments bluntly refused to go that far north and took position on

the south flank of the Dutch. This led to more frustration and

deterioration of the morale of the already shaken Dutch troops. They

were promised French help, but that failed to materialise. As mentioned

above, the Dutch fell back again and so the French were forced to

withdraw. In addition, the French attempt to support the Dutch in their

effort to retake the Moerdijk bridge was foiled by the Luftwaffe.

When the Germans drew closer to the coast, reaching the province of Zeeland, the French main force fell back, basically towards the border with Belgium, a necessary move in order to prevent the Germans from attacking the rear of their army fighting in Belgium. However, part of the French force remained Zeeland.

When the Netherlands surrendered on 14 May 1940 Zeeland did not and to continued the struggle. However, what morale remained was soon drained after the remnants of the Peel division had passed through the Dutch lines telling the most horrible tales. Furthermore, many did not see the point in continuing the fight, now that the rest of the country had surrendered. To complicate matters the cooperation with the French was non-existent. The French did communicate with the Dutch, but thought the prepared forward line and main line of resistance poorly sited. Instead of supporting these lines, they set up their own positions. When the Germans arrived in front of the forward line it was abandoned without a fight.

The brunt of the attack now fell on the main line of resistance. The battalion commander was determined to make a stand and had a meeting with his company commanders. During this meeting the German artillery started shelling the position. The battalion commander ordered his company commanders to rush to their companies and hold fast. Soon after he got the word that two of them had remained with a neighbouring company, refusing to go back to their original companies. After an express order these officers set off again, only to stop, both at the command post of the first officer.

|

|

The second officer did not go further. Again an express, direct order from the battalion commander was necessary to get this officer on the move. As soon as he had finally reached his company, he took it with him in an unauthorized retreat. Seeing this the other company commander left his command post following suit, not being bothered by the fate of his company. His men however soon noticed his departure and followed his example. Thus the main line of resistance became untenable and the few remaining defenders withdrew before the Germans could attack. The French were outraged and nicknamed the Dutch ‘boches du Nord’, the Germans of the North. |

|

Now that the Dutch main line of resistance had fallen Zeeland practically lay open for the Germans. The French withdrew to the south and took up position on the south bank of the Sloedam. They were supported by those Dutch troops still willing to fight. At least the command structure had improved, now that the French had taken overall command.

The Germans attacked the Sloedam in force and were thoroughly beaten back. The Germans drew up artillery, bombarded the Franco-Dutch position and were again beaten back. Then the Germans called for a Stuka air strike.

|

|

|

Now the French experienced what many Dutch had already undergone.

Material damage was limited but the morale of French and Dutch alike was

broken. The third German attack over the Sloedam went like a hot knife

through butter. For French and Dutch it was ‘Sauve qui peut’ (Every man

for himself).

The Battle of Mill and Brabant

As mentioned before, the Germans had to breakthrough the Maaslinie and the subsequent Peel-Raamstelling fast in order to link up with the airborne troops of General Student and breach the Southern perimeter of Vesting Holland. The early warning units along the border had done their job, resulting in many destroyed bridges. However, some fell intact into German hands, either by sheer speed or by ruse de guerre using German Brandenburger commandos in Dutch uniforms. The most important result for the Germans was the capture of one railway bridge. This allowed an armoured train, followed by an armoured troop train, to advance towards the Peel-Raamstelling, more precisely: towards Mill. For both parties Mill was the key to taking the Peel-Raamstelling.

|

|

The defenders of the Peel-Raamstelling had been alerted and had manned their positions when a train appeared. Open-mouthed, they watched it approach, wondering when the Dutch army acquired such trains. In fact, the Dutch army did not have any armoured trains, which dawned upon the defenders once both trains passed through their positions. The Dutch did have an excellent Anti-tank defence, named asparagus. These were steel beams that were lowered at an angle into slots in the track bed. Once primed only engineers/pioneers could remove them with heavy gear. For this reason placing and priming was not done without proper authority.

|

|

As the order had not yet been given, the

asparagus weren’t placed and the trains could pass through the Dutch

positions unopposed. At a safe distance the German troop train unloaded

nearly a battalion of infantry. The trains thereafter made their way

back behind German lines. At least that is what they had in mind. After

realizing their mistake the Dutch were quick to install the asparagus

and for good measure dug up some mines and placed them on the rail road.

The work was just finished as the armoured train reappeared and was

then thoroughly demolished.

The German battalion split up into two forces, one of one company, one of two companies, each advancing on either side of the railroad. The single company was noticed by a lieutenant of a section of an 8-Staal gun battery. He asked permission, and received it, to turn his guns and fire upon this foe. Despite this fire the Germans pressed on. The lieutenant suggested to his captain that the full battery should join in. The captain tried in vain to reach headquarters. He was one of the first to experience the inadequate leadership of his divisional commander, who was more occupied in shifting his headquarters than leading the battle. Acting on his own initiative, the captain had the full battery turned 90 degrees and open fire. This proved enough to force the Germans back.

However, the other German task force managed to capture several bunkers and trenches by attacking from the rear. But, they failed to fully break the line, became pinned down, and had to wait to be relieved. Meanwhile, the commander of the Light division had started to withdraw part of his division towards Vesting Holland according to plan. These troops were to fight against the airborne troops around Dordrecht. The commander realized that a breach of the Peel-Raamstelling could jeopardize his withdrawal. He ordered a unit of motorcycle hussars to reinforce Mill and help to retake the bunkers and trenches. As the hussars set off, no one thought of informing the commander of the Peel-Raamstelling, nor the local commander at Mill. Both could have advised the hussars about a covered approach. As it was, the hussars attacked the German positions in the Peel-Raamstelling across an open field. Although this threatened the Germans, they were able to repulse attempts to retake the position.

|

The lack of a sufficient amount of bridges led to huge traffic jams around the available water crossings. All troops were in a hurry and disputed priority. It wasn’t until the German Feldgendarmerie took over traffic control that the situation improved. The only unit that managed to reach the Peel-Raamstelling in time was an infantry battalion. The regimental commander was concerned to relieve his ‘trapped’ train battalion and recognised the need for speed. The German infantry commander had to attack whatever the cost and it was made clear that there was no artillery support available. Reluctantly he obliged and set up a plan of attack.

|

|

|

Just as the attack was about to set off and much

to his surprise, a flight of Stukas appeared, attacking both Mill and

Dutch positions to the North. This attack had been requested by a

neighbouring German unit that was held up by fire coming form Mill.

As before, the effect of the Stukas did more damage to the Dutch morale than to the Dutch positions. Once the Germans attacked many Dutch soldiers left their positions and fled, both rank and file and officers. Meanwhile the divisional commander failed to properly command his troops. As his command crumpled before his eyes he ordered a full retreat to a second defensive line. In fact, the retreat became a rout. The troops at Mill however did not receive the order and stood their ground until they were almost surrounded.

The second line of defence proved to be inadequate and Dutch morale was now very low. This was not helped by the fact that the promised French support did not materialise. As soon as the Germans arrived and showed some aggression most of the Dutch troops looked for refuge further back. There were examples of companies that stood their ground but had to withdraw when they became in danger of being cut off because neighbouring troops had already fled.

A third line of resistance was ordered. In the chaos this order was not received by many troops and this line never materialized. The Peel-Raamsteling had been breached in one day. The German armoured column destined to relieve the paratroopers had been able to race towards Moerdijk almost unhindered. But, after that they would meet more spirited opposition.

The eventual French support did not prove to be what the Dutch had expected. One negative factor was that no provisions had been made for coordinating the actions of both armies. To make matters worse, the Dutch High Command had assigned the commander of a division in full retreat with the extra task of coordinating with the French.

The battle for the Grebbeberg

The Grebbelinie (Grebbe Line) was the main defensive position of the Dutch army. This eastern wall of Fortress Holland stretched from the IJselmeer to the Grebbeberg by the Rhine. This line lay east of an old Napoleonic line which had been ‘modernised’, called the Nieuwe Waterlinie. It was between these two lines that Generaal Winkelman had to choose. The Grebbelinie was fortified with WWI style trench systems with the front line containing most of the pillboxes and heavy weapons, while the weaker stop line was designed for the front line troops to fall back to, and counterattack from if the front line was compromised. The Grebbelinie had to be defended with all the manpower and means available. Their motto was: ‘to the last man, and the last bullet.’

With a height of 52 meters the Grebbeberg, was referred to as ‘mountain’ by the Dutch. Nonetheless, it was a strategic position with visibility over a vast area. The Germans decided to concentrate their attacks on the defensive line here and had two advantages. The zoo on top of the hill had a tourist lookout tower which German spies made extensive use of in the days before war. Secondly, the area in front of the Grebbeberg had restricted fields of fire because of local orchards and farmhouses. The government wouldn’t permit the removal of these because compensation would have to be paid to the owners. Defence of the Grebbeberg fell to the 8th Infantry Regiment, with support from the division’s machine guns, mortars and Antique 6-Veld artillery. Behind the mountain around Rhenen stood sixty guns of 75mm, 105mm, 120mm and 150mm, all with pre-plotted co-ordinates along expected lines of advance.

Opening Moves

With the frontal attack on the Grebbeberg the Germans intended to keep the main Dutch Field Army occupied whilst the German airborne troops and fast armoured troops made their flanking move towards Rotterdam. Nevertheless the German High Command needed and expected a swift break through, The German 207th ID reinforced by SS Standarte Der Führer planned to punch through the defences on the IJsellinie and take the Grebbeberg on the first day. Their armoured trains had been stopped or destroyed and they had determined defenders to contend with in several places. Even after they had broken through the IJsellinie, the cavalry of the 5th Hussars delayed the Germans with ambushes and skirmishes, finally falling back to the front line trenches in the evening.

Already behind schedule, the SS troops prepared to storm the Grebbeberg. At 0200 the German artillery unleashed hell on the Dutch positions in a four hour barrage. At dawn the SS infantry attacked the ‘weak’ area in front of the main line, this area was dotted with many command posts and observer positions, the radio operators in these positions discovered that most of their communications had been severed by the German bombardment. These positions were still able to put up stiff resistance and the SS became frustrated that after a position was taken another one blocked their path. Some prisoners were either shot outright, used as labour to drag infantry guns or herded in front of attacking units as living shields. As darkness fell the German command could only look on in frustration as it took one whole day to clear this weak area and even so the front line still stood intact.

Due to the lack of good intelligence the Dutch Corps commander General Harberts firmly believed that they were facing no more than a few dozen bold Germans, rather than two full SS battalions, and the Dutch 4th Division were ordered to retake the forward positions during the night. The SS Standarte Der Führer commander of the 3rd Battalion, Obersturmbannführer Wäckerle also planned a daring night attack on the front line trenches. Artillery from both sides pounded the area in preparation, but the ensuing chaos meant that both night attacks were foiled.

About midday the German artillery bombardment on the front line ceased. The SS 322. Regiment, which had been using the ditches and the side of the dike to creep into position, stormed the trenches with sudden ferocity. The defending troops and pill boxes in the front line threw everything they had at the SS but the fearless stormtroopers kept on coming. Once the single line trench was breached it was relatively easy for the Germans to roll up the position and the defenders were forced to withdraw to the reserve line or face attack from three sides.

At the same time the Dutch air force managed some strafing runs and bombing raids on the German troops on the roads and their artillery, raising the morale of the Dutch troops.

With the front line crumbling the commander of one of the two infantry battalions that defended the Grebbeberg, Major Jacometti, rallied about a platoon defending the stop line and started a counterattack. He led the way, shouting: “DOWN WITH THE JERRIES” but this brave attempt was repulsed and Major Jacometti was killed by the overwhelming German fire.

By the end of the day the SS had been ordered to withdraw and rest for a planned flanking night attack on Achterberg, while regular Heer troops replaced them on the front line, ready for an assault on the reserve line at dawn the next day. SS Obersturmbannführer Wäckerle was determined to prove the SS could finish the job. He gathered a task force of about 200 men and launched a surprise night raid on the reserve line, the SS shock troops punched through the line along the road. Using POW’s as cover they tried to push into Rhenen over the railway viaduct. The attack was repulsed and the reserve line was restored cutting off the SS troops. Wäckerle was wounded and with about 50 survivors barricaded themselves in a nearby factory.

The Dutch also planned a flanking night manoeuvre through Achterberg, but due to delays it wasn’t until 0700 before four battalions of exhausted Dutch reinforcements made the counterattack from the North. The Dutch air force strafed the German positions and artillery in a coordinated attack. The SS were also making their flanking attack at the same time and both forces smashed into each other, the SS dug in and used their machine guns in strategic positions to pin down the Dutch assault in the open ground between the defence lines. The counterattack had failed and morale was beginning to fall, when suddenly the air was filled by a terrible shrieking noise as 27 Stuka dive bombers hit the Dutch positions. The Dutch troops fled in panic at the sound and effect of the screaming aircraft.

Meanwhile the German 322 IR assaulted the reserve line on top of the mountain, but the Heer troops were beaten back. A second attack saw the stop line dissolve into brutal hand-to-hand fighting with bayonets and grenades. Major Landzaat 8RI Battalion Commander held his Command post near the entrance to the zoo with grim determination. Once all ammunition was used up, and the building was beginning to collape around them, he sent the survivors away thanking them for their heroics. According to legend he then charged the enemy with a pistol in each hand. However the story could not be authenticated. Afterwards his wife found his charred body in the burned down rubble of his HQ. Authentic or not, for his conduct he was rewarded the Militaire Willemsorde medal, the highest Dutch military award.

The trapped SS group disguised themselves as Dutch troops and tried to cross the viaduct over the railway line, but the Germans were given away by their boots and repulsed. A second attempt also failed and Wäckerle himself was wounded a second time.

By this point the Dutch high command knew the Grebbeberg was lost and retreated with 50,000 troops leaving a thin screen to fool the Germans. The Germans prepared for an assault on the city of Rhenen. After a preliminary bombardment they assaulted only to find the city deserted. The battle for the Grebbeberg was over and symbolized the stoic determination of the Dutch defenders. The Germans named the hill ‘Teufelsberg’ (Devil’s Mountain).

The North

The northern provinces of the Netherlands were only lightly defended. The German progress was swift until they reached the first seriously fortified defensive line, the Wonsstelling. This position covered the approach to the Afsluitdijk. With mounting pressure from superior numbers this line was eventually breached. The Afsluitdijk was the gateway to the province Noord Holland, part of the Vesting Holland. When it was made two formidable fortifications were constructed, not unlike the later Altantic Wall. As the low Defence budget could not bear this, the costs were included in the costs to build the dyke itself, to be paid by another ministry, and thus were no affected by Defence budget cuts. Kornwerderzand was armed with four 50mm guns and 21 Schwarzlose HMGs. In the nick of time a couple of AA guns and AA machine-guns were added.

For the Germans Kornwerderzand was only accessible along the dyke. Even more important, the commander of Kornwerderzand had kept the morale of his troops intact despite the fact that all day long fleeing Dutch troops had passed the position claiming that all was lost. The resistance at the Wonsstelling had bought the defenders the necessary time to have Kornwerderzand fully prepared.

As the Germans were aware of the strength of Kornwerderzand they did not charge headlong into it. Instead they tried to bomb the position into submission first. But, the newly acquired AA defence proved to be a nasty and efficient surprise. Next, the Germans undertook a reconnaissance in force supported by artillery. The Dutch commander let the Germans advance to about 800 meter from the Dutch positions before opening fire. This forced the Germans to withdraw losing three dead and many wounded. Despite the limited loss of life the Germans were so impressed that they dubbed the dyke ‘Totendam’ (death dam).

More German artillery was brought up. As a countermeasure the commander of Kornwerderzand asked the navy for support. A ship with 150mm guns came to their aid. Helped by spotters in Kornwerderzand it silenced the German artillery. Only after the surrender did the Germans find out this fire did not come from Kornwerderzand itself, but from the Waddenzee.

By now the German commander had given up hope of taking Kornwerderzand and gave order to start preparations for crossing the IJsselmeer and land upon the coast of Noord Holland, leaving a small force in front of Kornwerderzand.

For the successful defenders of Kornwerderand, the order from the government to surrender came as a complete surprise, not to say a shock. They could not believe it to be true, but sadly it was.

~ Wayne & Victor.

|

Last Updated On Thursday, October 18, 2012 by Blake at Battlefront

|

|

|