|

|

|

|

|

No Retreat: The Siege Of Küstrin, 1945

|

No Retreat!

The Siege Of Küstrin, 1945

with Dr. Michael L. McSwiney

The city of Küstrin on the eastern bank of the Oder River has a long history dating back to before the 13th Century when the Knights Templar took over jurisdiction of the town and reinforced its castle. Through the centuries the town grew in importance as a trade and military hub changing hands on more than one occasion as the fortunes of the Prussian Crown waxed and waned. In the mid 19th Century, railways first came to Küstrin and the town quickly became a vital hub connecting east-west rail lines and northsouth rail lines.

|

| Learn how to refight the Siege Of Küstrin with Flames Of War here... |

World War II

During World War II, many German troops destined for the Eastern Front either passed through or embarked from Küstrin. However, despite the city’s importance as a rail hub and its numerous key bridges over the Oder River, Küstrin had been almost entirely ignored by Allied bombers so that even by January 1945, the city had essentially been spared the horrors of war.

As January 1945 progressed, Küstrin’s tranquillity was quickly shattered. Soviet Marshal Georgi Zhukov launched his Vistula-Oder Offensive on 12 January, 1945. Attacking from the bridgeheads across the Vistula river initially formed during Operation Bagration, the Soviet advance was rapid, despite continual supply issues. By 20 January, 1945 the first refugees began streaming into Küstrin.

By 31 January, infantry of the First White Russian front had crossed over the frozen Oder River and established a bridgehead at Kienitz, roughly 15km north of Küstrin; their armour was unable to safely cross the ice. The city soon found itself isolated as essentially a German bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Oder River with strong Soviet forces attempting to surround it.

|

|

Festung Küstrin

In a desperate attempt to stem the Red Tide, Hitler once again designated certain cities as fortress cities. Festung Küstrin was therefore established on 25 January 1945.

At that point, the city was a fortress in name only with few troops available to actually defend it. The local Volkssturm (People’s Militia) and police were quickly impressed into service by the local commander, General Raegener, and the city enhanced its existing defences by digging earthworks in the frozen ground.

The garrison was poorly equipped with only a few light anti-tank guns and artillery pieces. Berlin had promised 8.8cm FlaK guns, but these had not arrived. The town did receive a small boost in the form of several Pantherturm (Panther turret) bunkers, but many fell into the hands of the advancing Soviets before they could be set up in defensive positions. Despite the rag-tag nature of the defence, initial Soviet attempts to capture bridges for their armour over the Oder were readily repulsed.

|

| East Germany, 1945 |

|

First Line Of Defence

With so many Soviet bridgeheads across the Oder, the Germans realized that Festung Küstrin was one of the few obstacles in the way of a Soviet march to Berlin. German defences quickly stiffened and several fire brigades were dispatched to bolster the lines and disrupt the Soviet advance by assaulting their vulnerable bridgeheads on the western banks of the Oder.

By 31 January 25. Panzergrenadierregiment, including Panzer Abteilung 5, had reached Golzow to the west of Küstrin with a few elements reaching the city itself. The vaunted 21. Panzerdivision would arrive a few days later. Panzerdivision ‘Münchenberg’ was also created from the survivors of several experienced units and committed to the front, but it was held in reserve until March.

The elements of 25. Panzergrenadier immediately found themselves under attack by leading Soviet armoured elements as they detrained at the city’s rail station. The panzergrenadiers quickly jumped into action and blunted the Soviet assault in the town’s streets using Panzerfausts. With the immediate crisis and threat to the town alleviated, the panzergrenadiers were pulled to the west side of the river to assault the Soviet bridgeheads.

|

|

Kienitz

An initial attack on the Kienitz bridgehead was carried out by Gruppe Schimpf which consisted almost entirely of rifle infantry. As Gruppe Schimpf was advancing, the Soviets attempted a breakout from the bridgehead with armoured support. The German infantry was no match for the well-equipped Soviets and only the timely arrival of 119. Panzergrenadierregiment and Colonel Hans-Ulrich Rudel’s tankbusting Stuka squadron forced the Soviets back to their bridgehead.

Gross-Neuendorf

On 2 February, the Germans launched an armoured assault against the Soviet bridgehead at Gross-Neuendorf just to the north of Kienitz spearheaded by Panzer Abteilung 5 and Panzerjäger-Abteilung 25. Taking advantage of their air support, the Germans made strong progress entering the town itself, but soon came under fire by Soviet anti-tank guns, which ultimately drove the attackers back and preserved the Soviet bridgehead over the Oder.

|

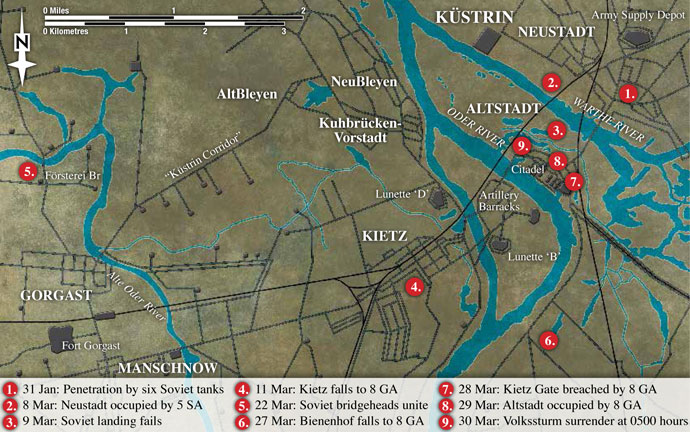

| The Küstrin Battlefield |

|

Soviets Consolidate

The Soviets had been able to take advantage of the cold conditions to fortify their bridgeheads with substantial anti-tank and infantry assets along with a fair amount of armour.

By 3 February, they had merged several of their bridgeheads north of Küstrin into a single bridgehead which could be more easily defended. For several days, they continued their build-up in the face of nearly constant German counterattacks, but by 6 February the weather turned against the Soviets.

German Build-up

A sudden thaw broke up the ice on the Oder River allowing the Germans to complete their defences. Rains over the next several weeks hampered military operations on both sides.

Belatedly recognizing the threat to Berlin, the Germans responded decisively with a strong build-up of FlaK guns atop the Seelow heights—an over 50-meter tall ridge with a commanding view of the entire Oder valley, including all of the Soviet bridgeheads.

The Soviets therefore found themselves in flat lowlands with the fortress city of Küstrin to their rear and the fortified heights to their front. The Germans on the Seelow heights could now easily observe all Soviet movements from their bridgeheads, and their guns could pound the bridgeheads mercilessly with little chance of Soviet counterattack.

|

|

Removing A Thorn

Unable to attack into Germany from their besieged bridgeheads, the Soviets attempted to complete the encirclement of Küstrin to remove that threat. At this point, the Germans still held a corridor which connected the western Oder defences to the city itself. Sensing an opportunity, the Soviets repeatedly attacked the corridor and managed to briefly cut off the city. However, by 7 February 21. Panzerdivision opened up the corridor once again. On 10 February they were relieved by 25. Panzergrenadierdivision which would ultimately hold the Küstrin Corridor until 19 March 1945.

The Siege

Within the city itself, the inhabitants settled in to face the Soviet siege. Initially the forces arrayed against the defenders were fairly weak, but poor German intelligence did not permit them to take advantage of the thinly spread Soviet formations. On 2 February, General Raegener was replaced by SS-General Heinz Reinefarth who would command the garrison until the end.

The Soviets built their own trench systems outside the town to defend against any attempted break-out from the Kürstin bridgehead. From these positions, the Soviets assaulted the city. Over the first several weeks of February, the city’s defenders repulsed several attacks, but the city itself was soon left burning by the constant Soviet barrage as the besiegers closed in.

|

|

Concentrated Attacks

By 4 March, the weather finally improved and the Soviets made a concerted effort to finally close the corridor and cut Küstrin off from any relief. The stalwart German defence, with 25. Panzergrenadierdivision as its cornerstone, blunted this attack at the cost of thousands of casualties on each side.

On 19 March 1945, the Germans made a move which would ultimately seal the city’s fate. Exhausted by weeks of hard fighting, the Germans pulled back 25. Panzergrenadier for rest. The Soviets recognized that a key unit had been removed from the corridor and renewed their attack. Once again, they encircled the beleaguered city.

As one Soviet battle group attacked the corridor, another force began what was hoped to be a final concerted attack on Küstrin itself. Belatedly recognizing their critical error, the Germans counterattacked with the 25. Panzergrenadier and Panzerdivision ‘Münchenberg’ on 22 March and attempted to re-open the corridor, but these forces were only able to get to within 3km of the city before the attack was halted and ultimately called off. The Germans attempted another relief attack on 27 March, but it also failed.

|

|

The Final Blow

Inside Küstrin itself, the Soviets and Germans were engaged in brutal street fighting for control of the fortress. Hitler ordered the defenders of Festung Kürstrin to fight to the last man, but realizing the hopelessness of the situation, SS-General Reinefarth ignored this order and attempted a break-out with his remaining forces.

On the night of 29-30 March 1945, he and roughly 1300 of his troops finally managed to escape the Soviet cauldron, but the ancient city of Küstrin behind them had effectively been wiped out.

~ Dr. Michael L. McSwiney.

|

Last Updated On Thursday, May 15, 2014 by Blake at Battlefront

|

|

|