|

|

|

|

|

The Battle for Stalingrad

|

The Battle for Stalingrad

The city of Stalingrad was founded more than 400 years ago as the Russian empire expanded its reach across the Asian continent. Hardy Cossack frontiersmen established it at the crossroads of both land and water. The new city was named Tsaritsyn.

In the second half of the 19th century the city’s development increased, turning it into the largest commercial and industrial centre in the Lower Volga region. In 1925 Tsaritsyn was renamed Stalingrad.

|

|

The legendary victory of the Soviet army at Stalingrad marked the turning point of World War II. The Battle of Stalingrad lasted 200 days - from July 17, 1942 through February 2, 1943.

The Drive on the Volga

During the winter of 1941-42, the Russian front stabilized. It was decided that German Army Groups North and Centre would hold while Army Group South would drive towards the Volga river and the important oil fields of the Caucasus, this plan was Operation Blue. Hitler touted it as the knockout blow that would finish the Soviets off.

|

|

|

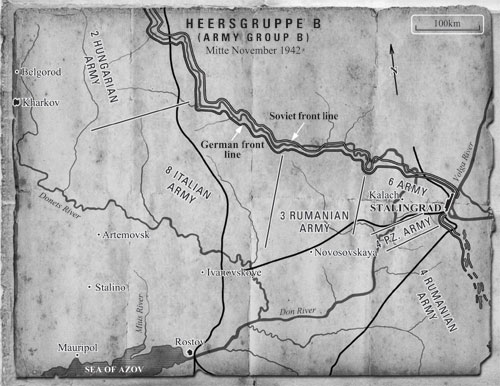

A reorganisation of the German forces was undertaken. Hitler dismissed Field Marshal von Brauchitsch as Commander-in -Chief of the Army, and assumed the position himself. The army group commands were reshuffled and Army Group South was split into two for Operation Blue (Army Groups A and B).

Army Group B (Heersgruppe B), consisting of Friedrich Paulus’s 6th Army, and the 4th Panzer Army of General Hermann Hoth, were to sweep through the corridor separating the Don and Volga rivers, swing Northeast and capture the city of Stalingrad, cutting the Volga river.

|

|

This force was fleshed out with the addition of armies from Germany’s allies, Romanians, Italians and Hungarians.

Army Group A (Heersgruppe A), under the command of Field Marshal List, with Field Marshals von Manstein and von Kleist in command of their armies, would fan out through the Transcaucasus, heading for Armavir, the oil-fields at Maikop, and the Caspian Sea.

Operation Blue opened in July 1942 and ran into stiff resistance almost immediately.

|

|

|

Although the Red Army was still struggling to

match the Wehrmacht on equal terms, stiff resistance at Voronezh did

manage to delay the German’s timetable. The brief respite from the spirited defence of the city allowed the bulk of the Russian forces to withdraw into the Russian interior.

Despite the delay at Voronezh, the German forces continued to round up thousands of prisoners as they push further into the south of Russia. Operation Blue was going so well. Hitler decided that the 4th Panzer Army was no longer needed to capture Stalingrad. He gave orders to detach it from the drive to the Volga, and join the assault upon the oil fields with Army Group A.

|

|

The 4th Panzer crossed over the 6th Army’s line of march. The ensuing traffic jam took several days to untangle. When it was sorted out, the 4th Panzer had also commandeered a large proportion of the fuel intended for the 6th Army. Paulus’s armour stalled for lack of fuel, and logistical problems kept the drive halted for nearly 2 weeks.

Hitler subsequently changed his mind again, and ordered the 4th Panzer Army to rejoin the 6th Army. The delay allowed General Andrei Yeremenko, commander of the Soviet Southern Front, to formulate a strategy to hold the Axis armies on the west bank of the Volga.

|

|

His armies were still demoralised by defeat, and an enemy force of

nearly 750,000 men was approaching what would be the Red Army’s last

line of defence.

On the other hand the German commanders found the lack of opposition ominous, as was the fact that their left flank was growing more dangerously exposed with every mile they advanced. The Soviets disappeared across the horizon, withdrawing towards Stalingrad.

The Battle for the City

Paulus’s 6th Army fought its way across the River Don and, on 23 August, were on the right bank of the Volga north of Stalingrad and moving into the suburbs.

|

|

|

Opposition from the Soviet Sixty-second and

Sixty-fourth Armies in Stalingrad stiffened, the 6th Army gained

control of the gap between the Don and the Volga, established air and

supply bases there and, on 2 September, made contact with Hoth’s 4th

Panzer Army.

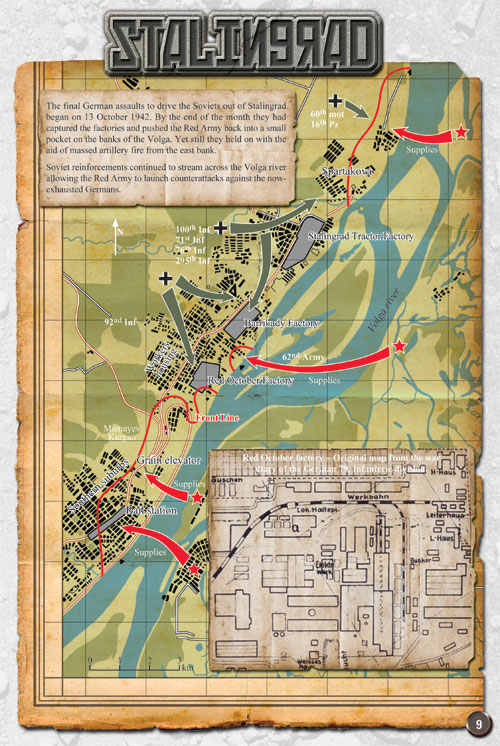

Despite several days of heavy fighting and many bombing raids, the Soviets, under Lieutenant-General Vassali Chuikov, tenaciously defended the battered city. The German Army High Command, concerned about the inadequacy of the forces supposedly protecting the 6th Army’s left flank along the Don (the Hungarians, Italians and supporting German units), advised withdrawal from Stalingrad to consolidate the line and prevent any chance of Paulus’s 6th Army being cut off by a Soviet breakthrough. Instead Hitler transferred units from the weak Don sector to the 6th Army and ordered it to capture the city.

Backed by Luftwaffe bombers, German infantry and armour made a mass assault through the crumbling streets. Every metre of the way was contested by the Russians in fierce house-to-house fighting, through the rubble-strewn streets, cellars, and sewers.

|

|

The grim determination of both sides characterise the prolonged and bloody struggle for the city.

Infantry dominated the battle, mountains of rubble, destroyed buildings and industry made it difficult for tanks to operate. After a week of intense fighting, the Germans managed to reach the city centre. A few days later, 6th Army troops fought their way into the industrial sector in the north, but on 29 September the Soviets threw them out.

The Germans regrouped and reinforced and 14 October tried again to break the Soviet defences.

|

|

|

The Soviets were at first greatly outnumbered

and forced to relinquish ground, they were able to ferry reinforcement

sand supplies across the wide Volga during the nights.

By 24 October, the 6th Army had fought itself to a standstill in the north of Stalingrad without ejecting its stubborn defenders. Little was now left of a city that had once housed nearly half a million people.

The German assault had deprived the Soviets of its industrial south-north communications. Both railway and river traffic were interrupted.

|

|

The Soviets hit back

The defeat at El Alamein and on the US landings in Morocco and Algeria, threaten the Axis forces in a dangerous pincer grip. This German setback came as a bonus for Marshal Georgi Zhukov, who had been preparing a Russian counter-offensive against the Germans in the south. The Soviets had built up vast reserves poised to unleash them on the arrival of the harsh Russian winter.

On 19 November, a massive Soviet attack (Operation Uranus) surprised and then overran the Romanian 3rd Army northwest of Stalingrad, exposing the left flank of the Sixth Army, just as some German generals had feared during the summer. 24 hours later, 160km/100mls to the south, the Soviets routed a mixed German and Romanian force guarding the 6th Army’s other flank; the two Soviet assault groups joined up within four days. General Paulus and his 6th Army, comprising 200,000 fighting men and some 70,000 non-combatants, were cut off.

|

|

Hold On

The Army High Command begged Hitler to allow the 6th Army to make a break westward while the Russian ring was still not firmly established. But the Luftwaffe chief, Herman Goering, claimed his aircraft could fly in 500 tons of supplies a day to the surrounded 6th Army. Hitler grabbed at this offer of a lifeline to Paulus and on 24 November ordered him to fortify his positions and await relief.

Three days later Field Marshal Erich von Manstein was placed in charge of the ad-hock Army Group Don, with the brief to relieve Stalingrad. He was not, however, allowed to create an opening to allow the 6th Army to withdraw. He was ordered to go in and stabilize the German front line in the beleaguered city.

Manstein set out on his mission on 12 December and arrived 48km/30mls outside Stalingrad on the 21 December. Knowing that the Soviets were closing in on him and he would be unable to hold his position for too long, Manstein took it upon himself to order Paulus to break out and link up with him before it was too late. But Paulus decided that in the absence of a direct order from Hitler to evacuate Stalingrad he must stay where he was.

The End of the 6th Army

The relieving force fell back, fighting, and the last tragic phase of the Battle of Stalingrad began for the doomed 6th Army.

|

|

|

Crushed in an ever-tightening grip by the

encircling Soviet armies, with inadequate supplies and winter clothing

in sub-zero temperatures (Goering’s promised daily airdrops proved

ineffective), Paulus’s rapidly shrinking army continued its grim

struggle. By the end of December the army had resorted to eating their

horses. Paulus flew out a personal envoy to see the Fuhrer with a

first-hand account of the deplorable condition of the 6th Army. Hitler

merely ordered him to hold out.

On 8 January, Lieutenant-General Konstantin Rokossovsky offered Paulus surrender, but he refused. Two days later the Soviets commenced a full-scale assault on the 6th Army’s last positions.

|

|

As the Soviets closed in on his exhausted and dispirited troops, Paulus contacted Hitler and told him that his situation was hopeless. After the war, Paulus said the Fuhrer replied, “Capitulation is impossible. The 6th Army will do its historic duty at Stalingrad until the last man...”.

The end was swift. By 25 January the Soviets had overrun the last German airfield, preventing any further supplies and ending flights out for the sick and wounded.

Over the radio, which was the survivors’ only link with the outside world, news came on 31 January that Hitler had been pleased to promote Colonel-General Paulus to Field Marshal.

|

|

|

Later that day, the 6th Army made its final

broadcast, announcing the arrival of the enemy outside the headquarters

command post.

The new Field Marshal, exhausted, was forced to surrender most of what remained of his command to General Mikhail Shumilov of the Soviet Sixty-fourth Army.

|

|

Two days later, the German XIth Corps, which had been holding out in

pockets in the north of the stricken city, also surrendered. Almost a

million men marched off to captivity (very few of which were to return

home).

Hitler threatened to court-martial Paulus, but ultimately Hitler accepted responsibility for the sacrifice of the 6th Army. Close to 150,000 Germans had died, three times as many as the Russians admitted they had lost. All Paulus’s guns, motor vehicles and equipment had been captured and the Luftwaffe had lost 500 transport aircraft.

The German Army, though not a broken force in early 1943, never really recovered from the loss of an entire army, casualties of over a million already sustained on the Eastern Front further compounded this.

|

|

|

Hitler had overstretched Germany before the full

might of the Allies were assembled against him, and the Germans would

pay the price for his stupidity.

In 1945 Stalingrad was given the honourable title of ’hero-city’. The fighting from July 1942 to February 1943 had virtually destroyed the city, but by 1975 it had been entirely rebuilt.

In 1961, Stalingrad was renamed Volgograd.

|

Last Updated On Thursday, September 27, 2012 by Blake at Battlefront

|

|

|